In September I enrolled in the course Functional Programming Principles in Scala, taught by Professor Martin Ordesky, the creator of the Scala programming language. The course was run over 7 weeks through Coursera.

‘Functional Programming Principles in Scala.’

I’d been wanting to learn more about functional programming for quite a long time. I had read a little about Lisp, scheme and recently Clojure, so I was well aware of some of the concepts (Immutability, Higher Order functions), but only vaguely aware of some other concepts (Lazy Evaluation). I had never written any code in any of those languages. This course seemed like the perfect opportunity to get me started, and it was.

Course Format

Each week between 5 and 8 video lectures, totalling between 1 and 2 hours length, were released to the website. Slides were also made available, although a lot of material was explained by Professor Ordesky during the videos, so you’d have a hard time trying to do the course without watching the videos. When watching the videos directly on the coursera website there were occasional pauses where you were prompted to answer questions, as a way to check you were understanding the material.

There was also a forum where people could ask questions, raise any issues, or just provide feedback. Many people had questions, which the staff and other students were generally quick to answer.

Detailed instructions were provided for setting up your scala development environment. The instructions initially included manually installing the scala eclipse plugin into your own installation of setting up eclipse, but just before the course started they were changed to use a pre-packaged build of the scala-ide from typesafe. In fact it was perfectly possible to use any IDE you like, or even a text editor such as vim or emacs. The benefit of using the example IDE was the inclusion of the scala “worksheet”, which is like an embedded persistent REPL inside eclipse, which is very convenient.

Course Assessment

The course was assessed via weekly assignments, with a soft and hard deadline (usually 1 week and 2 weeks after the release of the project, respectively). Shortly after the videos were released each week, a zip file of a scala project was also made available. Each project consisted of a skeleton of the implementation for the required tasks, as well as some unit tests written using ScalaTest. Our task for the assignment was to complete the implementation, according to the instructions and guided by the unit tests (sometimes the included unit tests were incomplete, in which case it was advisable to add your own).

The projects were to be submitted electronically using sbt – Scala Build Tool. Once submitted the students code would be automatically run against some unit tests (possibly different from the ones included in the project skeleton), as well as checked against an automatic scala style guide, and the grade would appear on the coursera website a short time later. You were allowed to submit as many times as you like, and your maximum score would be taken as your mark for the assignment. Submissions after the soft deadline would be penalized based on how many days after the deadline they were submitted. Overall this worked well. Some people had issues with the submission process in the first few weeks of the course, but once these were worked out it seemed to go smoothly.

One issue with on-line courses is cheating, and unfortunately shortly after the course started we received an email from the organisers saying that they had discovered cheating. It seems some students had been posting their assignment solutions on-line, despite agreeing to a ‘code of conduct’ that explicitly stated we were not allowed to do so. Some students on the forum said they had put their solutions in a public github repository either unwittingly, or being unaware of the code of conduct. It seems that some other students were using these solutions, rather than solving the problems themselves. Given that most of the (50,000) people taking this course were doing so for free, it seems rather strange to cheat, but I suppose the promise of receiving a ‘certificate’ saying you’d passed the course provides some motivation. Personally the most important thing for me was learning how to think “functionally”, and (hopefully) the impact it would have on making me a better developer, and I don’t think you’re going to learn that unless you work through the assignments yourself.

Impressions of the course

I thorougly enjoyed this course, and I think I learned a lot. As the course progressed I wrote about my impressions, and the high-level topics covered, on my google+ account. Here is a list of the posts, in chronological order:

- Week 1 – Functions and Evaluations

- Week 2 – Higher Order Functions

- Week 3 – Data and Abstraction

- Week 4 – Types and Pattern Matching

- Week 5 – Lists

- Week 6 – Collections

- Week 7 – Lazy Evaluation

If you’re interested to see more specific details about what the course covered, one of the other students, Albert Mata, also posted a series of very detailed articles covering the contents of the course.

Thinking Functionally

Without doubt the hardest part of the course for me was learning to think ‘functionally’ for some of the assignments. Following the video lectures was generally very easy, the ideas were presented in a logical order and Professor Ordesky used lots of examples, so it all seemed to make sense. Even learning Scala at the same time (I’d never used it before) didn’t seem to make the course any harder, the examples used just enough Scala to express the ideas. However when it came to actually apply the ideas myself, I realized how hard it was to actually internalize the ideas.

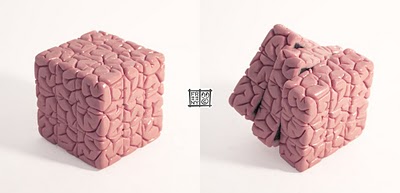

One example was the first assignment on recursion, which I was already familiar with, however the assignment was still quite challenging. The assignment was broken into 3 parts, of progressive difficulty. I found the first part trivial, the second interesting, and the last part quite difficult. For the last part, I felt quite ‘lost’ trying to derive the recursive solution from the problem statement. I think it took me 4 or 5 attempts before I figured out how to solve it. Of course, once you find the solution it seems easy, but actually getting there is the interesting bit. I had similar experiences with the last three assigments, which covered pattern matching, higher order functions, and lazy evaluation respectively. It really did feel like my brain was being ‘twisted’ to work in a way it had never done before.

‘How my brain felt before and during the assignments.’

In the end I got full marks on all the assignments, but I know I have a long way to go before I’ll be fully comfortable thinking ‘functionally’. The assignments had already been broken down into small functional steps, which I was able to solve (with some effort), but finding those small functional steps would be a much harder proposition. I believe (hope) that learning to do that is just a matter of gaining more experience with functional programming.

Impressions of Scala

I must admit to being very sceptical about Scala before taking this course. Even though I didn’t really know much about it, I had the impression that it was a very complicated language. This course was not really about Scala, Scala was just used as a way to implement the ideas of functional programming, and as such I can’t profess to know very much of the language. However, I can say that I was pleasantly surprised.

The main difference between Scala and most other statically typed languages (like Java or C++) is that Scala really is much more concise. Due to the type inferencing it often feels like a dynamically typed language (such as Ruby or Python).

One of the benefits of taking this course was getting to hear the explanations of some of these language features directly from Professor Ordesky. I have no doubt that Scala has been carefully designed (i.e. the consequences of decisions have been carefully considered), and a lot of thought has been put into how to make Scala a nice language to use.

I did hit a couple of cases where the compiler messages were a bit cryptic (reminding me of C++ template compilation errors), and the compiler does seem a little on the slow side. But most of the time the compiler errors were straight-forward, and the IDE integration seems reasonably solid.

Overall I found Scala a nice language to use, and would consider using it for future projects (I still need to learn more of the language to be capable of building non-trivial projects).

Further steps

Professor Ordesky mentioned in the last video that they are considering running a follow-up course with more advanced material. I hope they do, I will definitely sign up.

In the mean-time, I am attempting to work my way through Ninety-Nine Scala Problems, which Phil Gold adapted from Ninety-Nine Prolog Problems.

Overall

I found the course fantastic, and it seems a lot of people agree. Out of the 50,000 people who signed up, around 20,000 people submitted solutions for all 6 projects, so the participation rate was certainly very high. The course provided a great foundation in the basics of functional programming. I look forward to learning more about Scala, as well as other functional languages (Clojure and Haskell are on my list to learn). Professor Ordesky is a great teacher, and the course material was well structured and presented in a very logical manner. The focus of the course really was functional programming, but an additional benefit was learning some basic Scala, which I enjoyed using much more than I thought I would. I thoroughly recommend this course to any experienced developer.